Asset managers expanded into alternative investments for higher fees. Some ended up facing culture clashes and sluggish pickup from salespeople.

If there ever was a perfect moment for a mutual fund giant to leap into the hotter arena of alternative investments, T. Rowe Price Group Inc. seemingly found it. Its stock was soaring to record heights when executives picked their takeover target, Oak Hill Advisors.

The marriage hasn’t gone smoothly.

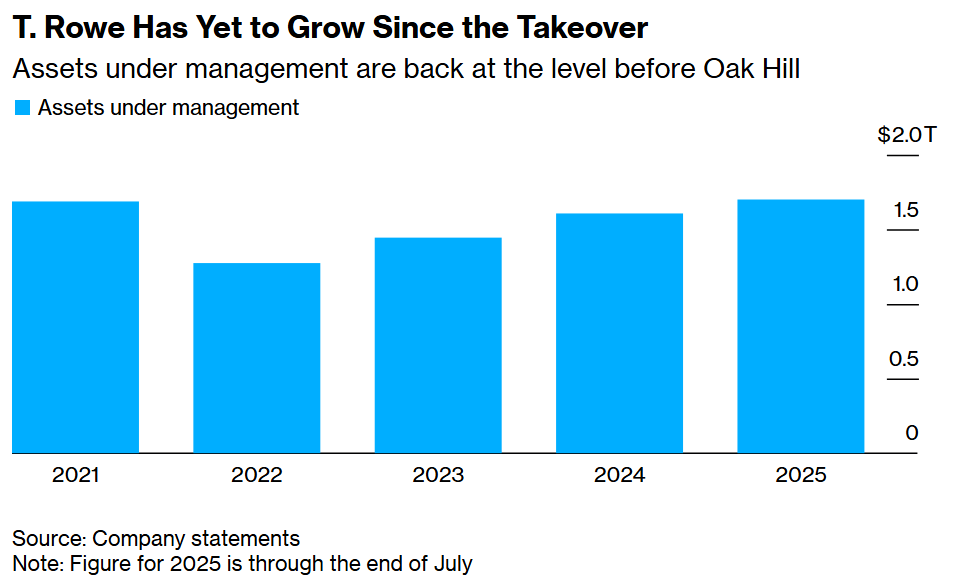

Combined assets are at the same level as four years ago, and the shares are down by almost half. Insiders describe a range of frustrations, with funds struggling to raise money and senior staff leaving.

This is now crunch time for traditional investment firms that once dominated Wall Street. With their mutual funds falling out of vogue, the asset managers made a slew of attempts to expand into private markets and other revenue-generating alternative investments by pursuing takeovers and partnerships that have yet to pay off. Executives atop an industry managing more than $35 trillion for pensions, institutions and everyday investors are under mounting pressure to try more drastic measures — from bigger deals to deeper cuts.

“It’s clear that some of these tie-ups won’t stand the test of time,” said Evan Skalski, a senior partner at Alpha FMC, which advises large asset managers. While some deals could eventually work out, “the road to success in this space will be strewn with failures of attempted partnerships and acquisitions.”

This month, T. Rowe struck a much different deal than the transformational acquisition it announced in 2021, when the asset manager was riding a pandemic-era surge in investing. This time, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. agreed to buy as much as $1 billion of the company’s stock. T. Rowe will work with Goldman to sell more private-market products to the masses. Goldman is accruing the stake with T. Rowe’s price-to-earnings ratio well below half the S&P 500’s average.

Traditional fund houses such as Franklin Resources Inc., Invesco Ltd. and State Street Corp. also are trying to find ways to sell hotter products that generate higher fees, through acquisitions or otherwise — but it’s not easy. Some have been left contending with wide gaps in executive pay or cultural divides in the ranks. Salesforces built to pitch plain-vanilla products proved slow to move riskier private-market offerings. And the competition is formidable, with incumbents such as Blackstone Inc., Apollo Global Management Inc. and Ares Management Corp.

One ray of hope for traditional managers is an initiative this year by the Trump administration to open up 401(k) plans to the types of alternative products that they have been aiming to sell more. Even then, larger alternative investment firms are vying to win market share, too.

The mutual fund industry’s attempted migration into alternatives was set in motion as customers switched to low-fee passive funds, forcing firms to whittle costs to compete in recent years. Mutual and exchange-traded funds now charge 0.3% on average, down from about 1% two decades ago, according to data from Morningstar Inc. Yet many private-markets funds for wealthy investors charge around 3%, and sometimes much more.

As a senior executive at a big asset manager put it: You can’t eat assets, you can eat revenue.

T. Rowe’s acquisition of Oak Hill was supposed to transform the company by bringing an expanded suite of products and strategies to its legions of existing customers. While Oak Hill has continued to pull in money amid a private-credit boom, one of the big justifications for the deal was that push into retail — and so far, that hasn’t worked out. The only retail private-credit fund that T. Rowe launched with Oak Hill had a net asset value of $2.6 billion almost two years after it was set up. It took Blackstone a single quarter to raise $3.7 billion of equity for its popular BCRED strategy.

Last year, the $1.7 trillion asset manager’s revenue was 7.5% lower than in the year of Oak Hill’s takeover, and net income was down almost a third, eroded by higher expenses. At least 10 managing directors have defected from Oak Hill to rivals in the past two years, and T. Rowe’s head of global alternatives left a few months ago, after just two years in the job.

In May, Chief Executive Officer Robert Sharps told analysts the acquisition of Oak Hill will bear more fruit. “There’s a very big opportunity over time to deliver OHA’s capabilities” to wealth clients, he said. “But it’s been intensely competitive and slower than we would have liked.”

A company spokesperson reiterated that faith in response to questions for this story: “We remain confident that T. Rowe Price’s relationships and OHA’s long and distinguished track record of managing private-credit portfolios is a powerful combination that will continue to drive the expansion of our private-markets business.”

Inside the combined firm, Oak Hill leaders including founder Glenn August have to meet economic and fundraising targets so that executives can collect up to an additional $900 million in perks. Though the rewards were slated to begin in 2025, T. Rowe had yet to assign them any value at midyear, regulatory filings show.

At his firm’s investor day a year ago, Apollo CEO Marc Rowan marked his industry’s decade of ascent with a slide showing that the market capitalization of alternative asset managers had quintupled since 2014, while the value of traditional firms stayed flat.

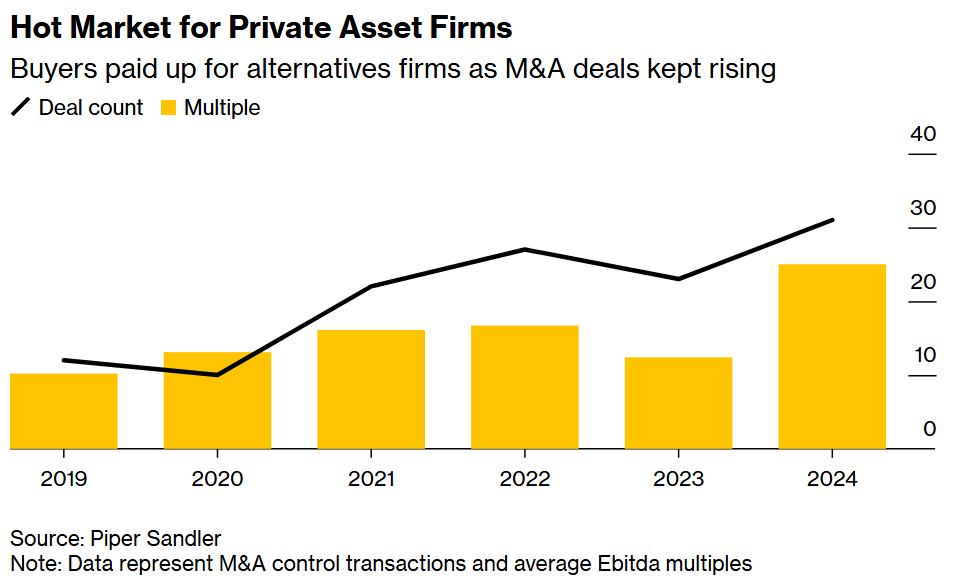

To fight that trend, standalone asset managers have splashed out more than $35 billion buying private-markets firms since 2021. In interviews, more than three dozen people close to several mutual fund powerhouses painted a picture of internal tensions and tempered expectations. The group — including current and former executives and employees, as well as investment bankers, consultants and lawyers involved in the deals — asked not to be identified because they weren’t authorized to speak publicly.

Many described tie-ups that began optimistically before encountering unexpected difficulty reorienting sales teams to handle more complicated private-market investments. Pay gaps have become an issue, as employees in low-fee operations become aware that they’re earning less than newly arrived alternative investment managers, who share in the juicier revenue generated by their deals.

Take Franklin Resources. The firm — about 40% owned by the billionaire Johnson family — set out to transform itself from a mutual fund shop into a conglomerate of investment managers and siloed alternatives firms. Since 2018, it has bought managers including Benefit Street Partners with a focus on private credit, Lexington Partners for secondary private equity stakes and Clarion Partners for real estate.

The spree helped Franklin amass $260 billion in alternatives and set up channels for new fundraising. The company pulled in $19 billion for alternative strategies during the first nine months of its current fiscal year. But that has done little to reverse a decade of outflows for the firm overall. In the past five years, clients have yanked more than $200 billion from its funds. Net income has declined in each of the past three fiscal years.

Franklin lets the boutiques it buys operate independently. Most still have their own CEOs, and some their own offices. In interviews, people who have worked in those outposts said they had little to no contact with Franklin, and a couple couldn’t remember the name of its CEO, Jenny Johnson, of the founding family.

In tense meetings attended by Franklin staffers, executives from Benefit Street openly expressed dissatisfaction over the pace of progress in the first few years after their merger, people who were present said. Benefit Street executives complained that Franklin’s sales fleet wasn’t doing enough to sell their funds to the multitrillion-dollar market of wealthy clients. Some executives even mentioned the millions of dollars they were earning a year, underscoring their clout to Franklin managers earning much less, witnesses said.

To spur sales, Franklin at one point upped the commissions for those funds, the people said. Johnson’s firm also hired more sales staff, and head of wealth management alternatives in the Americas, Dave Donahoo, is now coordinating private-markets specialists and generalist sales teams to raise more money across the asset manager.

The company said it aligns incentives to ensure that general and specialized sales teams collaborate and prioritize alternatives.

“Franklin Templeton has strategically expanded and diversified its platform to navigate market cycles and capitalize on strong momentum in areas like alternatives,” a spokesperson said in a statement. Units operate independently so they can hone expertise, but their personnel do meet with each other regularly and take advantage of the strengths of the broader firm, the spokesperson said.

Firms that tried expanding without acquisitions have faced challenges, too. At $2 trillion asset manager Invesco, where almost a fifth of customer assets are in a passive strategy that hasn’t been earning fees, executives encountered stiff competition when they set out to raise private-credit funds. The firm’s institutional salespeople attended hundreds of meetings with pension funds and other clients over a couple of years but struggled to raise money, people familiar with the efforts said.

Invesco hired a placement agent to help. Still, of the roughly $47 billion the firm says it has in private credit, only a small fraction is in a pair of pure direct-lending funds. The rest is in more liquid assets including conventional loans and distressed debt.

“We are proud of the support of our clients in the successful recent close of our $1.4 billion direct-lending strategy, the continued growth of our private-markets business and of our recently announced partnership with MassMutual and Barings,” Invesco said in a statement, referring to the amount in the larger of those two funds.

BlackRock’s Spree

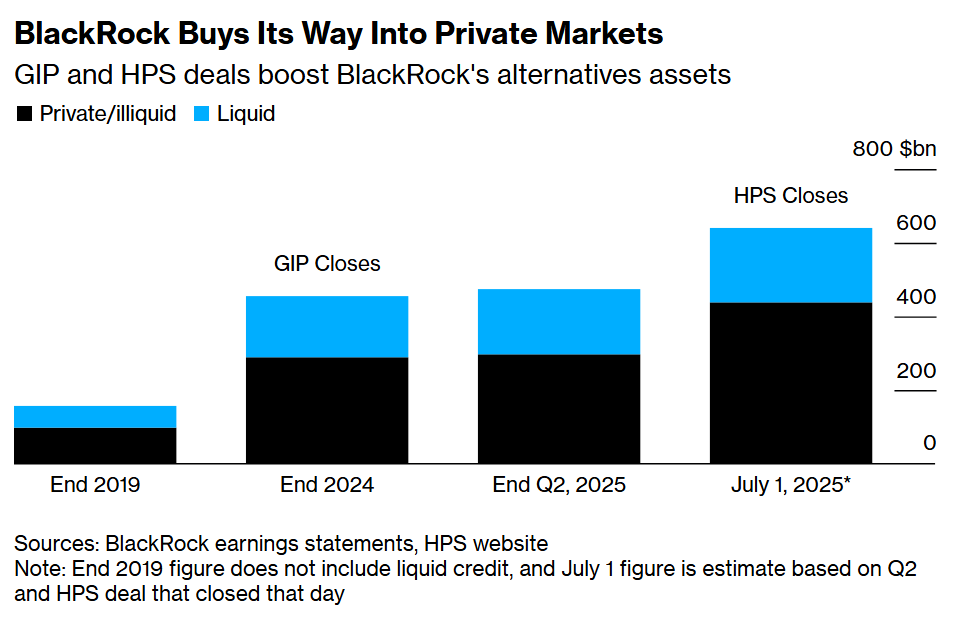

BlackRock Inc., the world’s largest asset manager, had more firepower for making the leap to alts and is betting big that it can make it work.

For years, BlackRock struggled to match the scale of the leading private-markets players. A 2018 purchase of alternative credit firm Tennenbaum Capital Partners led to chronic challenges, senior-level departures and the middling performance for some funds.

Ultimately, CEO Larry Fink opted for bold acquisitions, just as client demand started growing fast. In the span of 18 months, he spent almost $28 billion snapping up private-markets firms, including making the two largest-ever acquisitions in the space, spending $12.5 billion for Global Infrastructure Partners and $12 billion for HPS Investment Partners.

BlackRock’s acquisitions show how buying alternative money managers can create different centers of power. Arms that focus on private markets maintain some independence and pay generously to retain staff whose careers started in more aggressive banking cultures.

For customers, the experience will be seamless, Fink told analysts in July. “We are intentionally organizing to bring clients under one unified firm, not a collection of enterprises, and we have aligned our cultures and aligned each and everybody’s interests.”

Executives who joined through BlackRock’s purchases are richer than just about anyone else at Fink’s $12.5 trillion firm, including the CEO himself, who has a net worth of about $2 billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index.

BlackRock is looking to align executive compensation with how the likes of Blackstone and Apollo pay their bosses. Franklin and others are trying too, by creating different pay packages to hire Wall Street talent, according to a person with knowledge of their pay structures. But firms also have to fight off requests — sometimes even from their research analysts — who now want to get a share of fund profits.

Others have avoided the headaches of mergers and pursued joint ventures, launching hybrid funds for retail investors.

Capital Group, a $3 trillion active manager of stock and bond funds, spent about two years mulling a push into private assets. It opted for a tie-up with KKR & Co. and recently launched two funds that mix private and public credit. They had net inflows of $175 million as of Aug. 31.

“Our belief was that the burden of integration was so high,” Holly Framsted, who heads Capital Group’s product group, said in an interview, adding that the firm also decided against building its own private-markets business because of the difficulty and time it would take. “Our clients need solutions today.”

Elsewhere, Vanguard Group and Wellington Management partnered with Blackstone. Invesco joined up with Barings. State Street teamed up with Apollo. And almost everyone in the industry is looking to start expanding into private assets one way or another, according to Bain & Co.’s Markus Habbel, who runs its franchise advising the global wealth and asset management firms.

But coordinating partnerships has also proved treacherous. On the day that State Street’s investment arm launched a pioneering private-credit ETF with Apollo, regulators publicly expressed concerns about key aspects of the product that the firm rushed to resolve. State Street’s head of private markets exited in May just months after getting promoted to the role, as did another employee who led partnerships and initiatives at the unit. The departures were “completely unrelated” to the ETF or the firm’s continuing collaboration with Apollo, and turnover is normal in large companies, Chief Business Officer Anna Paglia said in a statement.

In a recent interview on Bloomberg TV, State Street CEO Yie-Hsin Hung said the $5.1 trillion firm is seeing “tremendous demand” for private credit. Six months from its debut, the ETF has assets of about $140 million.

Written by: Loukia Gyftopoulou and Silla Brush @Bloomberg

The post “Mutual Fund Titans Plowed Into Private Markets. It Isn’t Working” first appeared on Bloomberg