Funds stung by the property downturn limit client withdrawals, after assuring ordinary investors they were safe

Andre El-Baba never imagined an investment fund could trap him.

A lifelong property manager from Vancouver, he’d spent decades navigating real estate markets and thought he understood risk. So when he put money into Romspen Mortgage Investment Fund in 2022, it felt like a safe, sensible choice. Such private real estate funds had become a popular way for Canadians to invest in developing new houses and condominiums, riding a construction boom that had lasted two decades. They offered solid returns, regular payments and the ability to cash out at will.

Then the gate slammed shut.

Not long after he and his father invested a combined C$2 million ($1.5 million), Romspen announced it was blocking withdrawals — a last-resort tactic that lets funds avoid selling assets when too many clients want to pull out their money. The principal Andre assumed would always be within reach was suddenly sealed off, with no timeline for release. He’s getting only a thin, 2% stream of monthly income in return — far less than expected. Every month, Andre’s account statements tell the same story: The cash is still there, but he can’t move it.

“It’s been terrible,” said El-Baba, 47. “It’s not small change for us. It’s a lot of money.” Romspen did not respond to multiple requests for comment from Bloomberg.

Across Canada, investors who poured billions into private real estate funds suddenly can’t touch their money. Stung by a deep downturn in the country’s housing market, many of the funds have restricted cash distributions, client withdrawals or both, in a process the industry calls “gating.” Often, the companies don’t say when access will resume. About C$30 billion ($21.7 billion) — almost 40% of the C$80 billion invested in such funds — is now locked up.

The effects could be profound — and not just for investors like El-Baba.

Prime Minister Mark Carney wants to double the pace of housing construction, counting on builders to help Canada’s economy survive the US trade war. But real estate investors who can’t access their money may be reluctant to risk more. Disruptions to construction financing in the 1990s led to a period of lower home production, warned Diana Petramala, senior economist at Toronto Metropolitan University’s Centre for Urban Research and Land Development.

“Supply, once curtailed, does not simply bounce back,” she said. “It drags on for years.”

Nor is it certain that the gating wave is done. There’s a risk more funds will follow suit if their own, spooked investors start bolting for the doors.

“If the people at one fund suddenly can’t get their money out, the people at other funds start asking questions,” said Jamie Grundman, the head of multi-family office Irager Investments Inc. “This stuff spreads like wildfire.”

To be sure, this is not Canada’s Lehman Brothers moment. The development industry has other sources of capital, including C$13 billion of government money Carney plans to inject into a new agency to build affordable homes. But the gating crisis is a harsh reckoning for everyday Canadian investors, who for decades treated real estate as a safe bet.

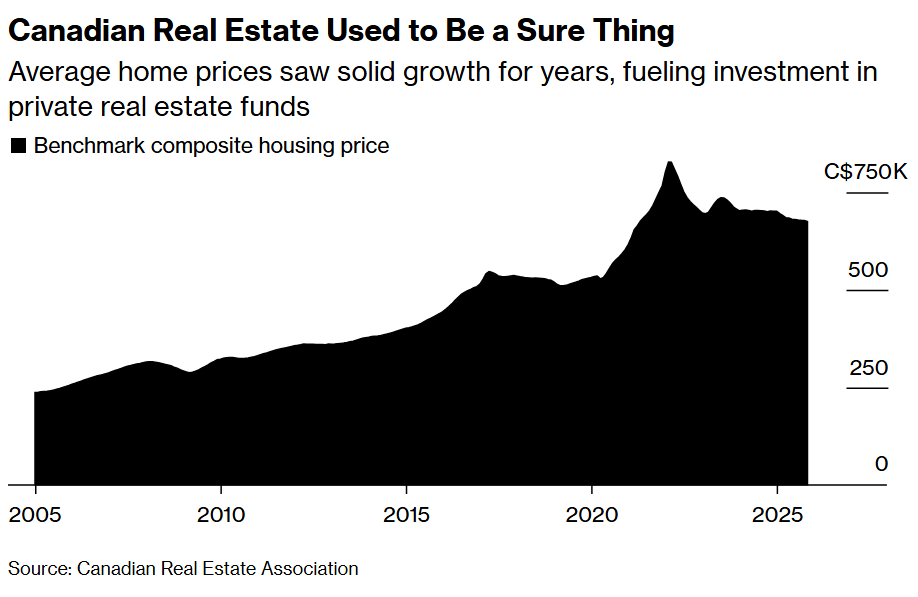

They had good reason. Canadian home prices rose steadily from 2002 through 2022, far outpacing inflation. Private real estate funds, once reserved for institutions and wealthy investors, started targeting doctors, dentists, teachers and retirees. Clients were told they could have it both ways, with investments that included the solidity of hard assets and the convenience of regular payouts. If they chose to pull out their money and invest it elsewhere, they could.

It worked while the market kept rising. Then came 10 interest rate hikes in 2022 and 2023. Condo values plunged by hundreds of dollars per square foot.

“Real estate is not the holy grail that people thought it was,” said Darren Sissons, a partner at Campbell, Lee & Ross Investment Management, a private wealth management firm that does not operate a real estate fund. “History has proven repeatedly that a sure winner doesn’t last forever.”

Falling prices laid bare a structural problem within the funds. Clients expected them to be liquid, but the assets they held — towers, warehouses, construction loans — were not. Carney, in his past job as governor of the Bank of England, warned in 2019 that funds offering frequent redemptions despite illiquid assets were “built on a lie.”

That fundamental mismatch explains the gating. As housing prices fell and new developments stalled out, the funds no longer generated enough returns to cover outflows. More money was heading out the door than coming in. Managers had little choice but to close the gates.

“You always want to be in a position to redeem 5% or 10% of assets, but to guarantee that, you’d have to leave cash sitting idle,” said John Nicola, founder of Nicola Wealth. Holding enough money to ensure quick exits for anyone who wants them, he said, would drag down returns for the vast majority of investors who want to stay in the fund. Ultimately, the managers’ obligation is to prioritize them over clients seeking to leave, he said.

In September, Vancouver-based Nicola Wealth told investors that withdrawals from two of its largest real estate vehicles would take longer than usual, blaming slower property sales and tougher market conditions. Those same funds, which together manage about C$2.7 billion, have also seen their regular cash distributions cut by more than a third, according to Nicola’s own reports.

The firm has not said when redemption timelines or payouts might return to normal, although John Nicola said increasing distributions is “a priority when conditions allow.” One smaller Nicola fund that buys, renovates and develops properties lost about 21% of its value in the first nine months of last year. The decline followed nearly a decade in which the fund’s property values rose steadily without a single down year, until falling sharply in 2025.

Once underway, the gating wave was hard to stop.

- Romspen Investment Corp. was an early mover in the current wave of restrictions, halting redemptions in 2022 and keeping them gated ever since.

- Hazelview Investments has suspended redemptions at least twice in its C$1.3 billion Four Quadrant Global Real Estate Fund since 2023, as withdrawal requests reached nearly 30% of assets. “We recognize that periods of limited liquidity can be challenging, and we work to assure investors that we are managing these conditions with diligence and transparency,” Colleen Krempulec, the head of sustainability & brand, said.

- Trez Capital froze withdrawals in August across five funds — representing C$2.8 billion in commercial real estate loans — while continuing monthly distributions. The company, in a statement to Bloomberg, said it was focused on reopening the funds in 2026 but did not give a specific date.

Other funds that have either halted or limited redemptions have included Centurion Apartment REIT — a C$7.9 billion vehicle focused on apartments, student housing, and real estate lending — and KingSett Capital’s Canadian Real Estate Income Fund, which in December restarted monthly distributions after a one-year suspension.

Temporarily shutting the doors gives fund managers time to conserve cash and reset their strategies, Sissons said. But it’s a shock to client confidence that can linger long after the initial jolt.

“As soon as you gate, investors stop believing you,” Grundman said. “Once you cross that line, people know you’re in a crisis, and they question everything else you tell them.”

Some funds are trying to preserve investor payouts by borrowing, pledging their portfolios as collateral to secure credit lines and then using that money to fund distributions, according to people familiar with the practice. Professor Jim Clayton, a longtime real estate scholar at York University’s Schulich School of Business, warns “that’s a bit of a house of cards.” Borrowing to pay distributions, he said, merely extends the illusion of stability while deepening the eventual reckoning.

The Canadian real estate market remains in such a slump that it’s difficult to see how the funds can quickly return to health. Prices have fallen 18% from their peak, according to data from the Canadian Real Estate Association. Development pipelines in Toronto and Vancouver have thinned to levels last seen in the 2000s. Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp. said it’s monitoring the gating trend but declined to comment on how it might affect future construction.

Meanwhile, population growth, the fuel for Canada’s housing demand, has fallen to zero after immigration curbs. Statistics Canada, the country’s national statistical agency, reported a 0.2% population drop in the third quarter of 2025 — the only quarterly decline on record outside of the Covid-19 pandemic in data going back to the 1940s. With fewer new renters and buyers, absorption of housing units is faltering.

Weak demand, in turn, makes all forms of financing for real estate development harder to obtain. Commercial real estate investment in the country dropped 22% year-over-year in the first half of 2025, according to a report from Altus Group. Economic uncertainty drove the pullback, the data firm said.

Petramala said a credit crunch in the industry now could lead to a housing affordability crisis in five or 10 years, once demand starts rising again.

“The long-term impact is that we may never return to the same levels of supply,” she said. “That means it will be much harder for families to get access to housing down the road, once the economy recovers.”

Written by: Paula Sambo @Bloomberg

The post “Canadians Are Furious After Real Estate Funds Lock Up Their Money” first appeared on Bloomberg