Mainstream economists have underestimated the cost of all the confusion the administration has unleashed, particularly on trade and immigration.

Many forecasters and investors misinterpret what is happening in the American economy. Some believe the uncertainty around President Donald Trump’s trade and other economic policies is abating, while a loud and influential minority argue that the administration’s deportations and tariffs are not causing the predicted harm. Inflation increased only modestly before coming down in 2025, they point out, while the latest data show the economy growing at its fastest rate in two years.

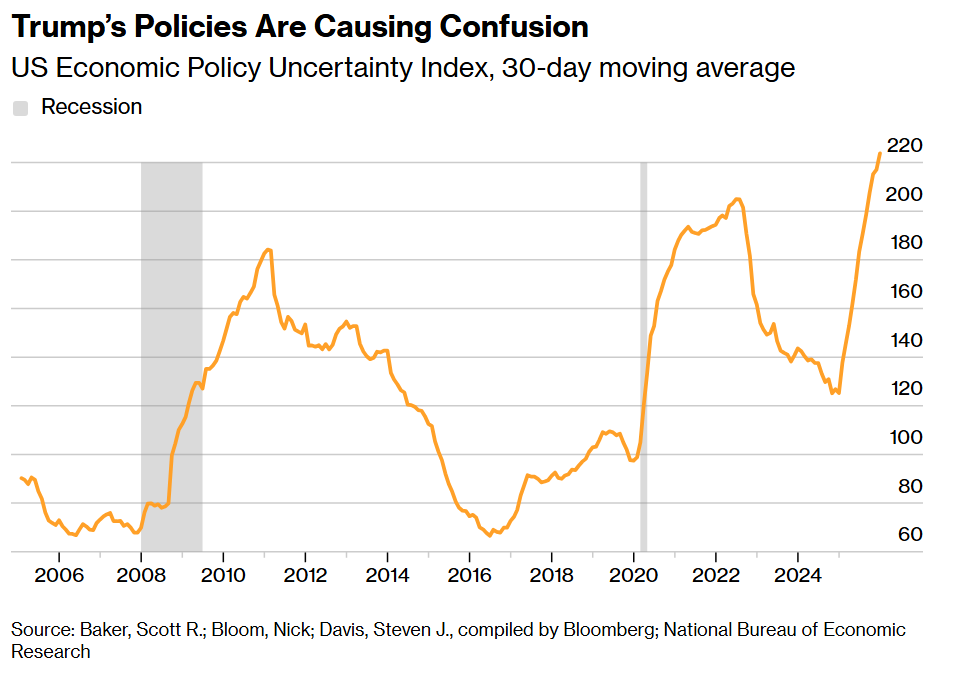

These mistaken assessments are based on a fundamental misunderstanding of how government-induced uncertainty affects the economy. This confusion makes sense because no presidential administration has imposed this kind of uncertainty on the US private sector in a century or more. The economy’s solid growth due to artificial intelligence investment further muddies recognition of these unfamiliar harms. Careful analysis, however, shows the stagflationary effects of Trump’s policies are kicking in and should become too evident to miss as we approach April 2, the first anniversary of his so-called Liberation Day.

It should be no surprise that it takes time before the paralyzing effects of tariffs and deportations on decision-making by businesses, households and investors start to surface in government statistics. In our analyses of the Trump economic program at the Peterson Institute, we consistently predicted that it would take at least a year before the impact was visible in macroeconomic data. My inflation forecast for 2026 is for the consumer-product index to rise at a 4% rate—perhaps even higher—by the third quarter, up from a 2.7% rate in November, the latest reading.

It may feel like a long time since Trump initiated mass deportations of undocumented immigrants and began blanketing imports with tariffs that vary wildly depending on the product and country of origin. Yet businesses have had many uncertainties to resolve before deciding how much to raise prices or whether to shift supply chains. Will Trump even go through with his tariff threats? If he does, will the tariffs be negotiated away in a later deal or struck down by the courts? If the duties stick, could my business or industry secure an exemption through political lobbying or expect a rebate such as the one Trump is offering farmers?

Then there are the supply chain considerations. Should I buy inputs from Mexico instead of China? Should I relocate production from China to a lesser-tariffed country? Should I bring production back to the US? Even the largest, most sophisticated manufacturers, such as Caterpillar Inc. and Toyota Motor Corp., have been hesitant to make significant decisions on reallocating production. And if the biggest companies—those with the most extensive analytical resources and global experience—are hesitant, how long will it take for small and medium-size businesses to react? Companies also bought time when they stocked up imports ahead of Trump’s trade war. But once those stockpiles run out, as has happened pretty much across the economy by now, they will be forced to pass on their higher costs to consumers.

Just as unprecedented tariffs take time to work through the economy because of lags in decision-making, so does a radical shift in US immigration policy. The Trump administration claims to have deported about 1 million undocumented immigrants over the first year of his second term, but what looks like the world’s most boring graph tells a different story.

Those flat lines show that employment levels in the US industries that are most dependent on undocumented labor—such as health- and child-care, agriculture, food processing and residential construction—have remained essentially unchanged since Trump took office again. This implies that large numbers of undocumented workers have not left yet.

Although tracking undocumented labor is inherently difficult, government data do not reveal a substantial number of native-born or foreign documented workers moving into these industries. These occupations have poor working conditions, pay low wages and offer little or no benefits, which is why they are dominated by migrant workers. To induce legal workers to take those jobs, employers would have to pay more. Yet wages in those industries have not been rising.

Robots are not ready and machines are not cost-efficient enough to replace low-cost human workers in areas like fruit and vegetable harvesting, home health- and child-care services, poultry processing, exposed mining and home construction. In any event, a surge in labor-saving investment in automation in these subsectors would be visible in the data, and there has been none.

Just as businesses need time to adjust to the Trump administration’s policies, so too do undocumented families. Think through the decisions they must make under this uncertainty, and that explains the delayed departures and lagging macroeconomic impact. First, will Trump really follow through on his deportation threats? Will immigration officers come after me in my neighborhood or at my workplace? If they do, how much can I earn before then? Should I leave on my own so I can apply for legal residency later? Do I take my family or not?

Employers that rely on undocumented labor have their own decisions to make. Arguably many businesses chose to risk US Immigration and Customs Enforcement raids because they could pay even less while their workers were under threat, and put off searching for new ones, albeit at some cost in employee turnover and no-shows. At some point in 2026, we should expect the reality to catch up with the administration’s claimed net outflow of migrants, though that number will include a lot of documented immigrants as well.

When it does, there will be shortages in some parts of the job market, forcing employers to raise wages to fill vacancies and thus adding to inflationary pressures. Home health-care costs, for example, are rising at a 12% annual rate according to the latest data, near the highest in decades. This could push some working women into part-time work or out of the labor force entirely to care for family members, as happened during the pandemic (though on a smaller scale).

Decision-making under uncertainty also explains the clear duality of investment in the US economy, with AI and related industries seeing a substantial rise and the rest of the economy showing near zero growth. The building boom in AI-related infrastructure is a prime example of what Nobel Prize-winning economist Robert Solow called “exogenous technological progress”—typically the advent of a new technology powering an expansion independent of the normal economic cycle. Capital expenditures on data centers, advanced chips and other AI gear were the principal driver of the expansion in gross domestic product in the second and third quarters of 2025.

But why should private investment in the rest of the economy be so weak when the tax code is becoming more favorable toward it (thanks in part to provisions in Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act); when real interest rates are low by historical standards and likely headed lower, courtesy of the Federal Reserve; when corporate balance sheets are solid and private credit is widely available; when energy prices are falling; when deregulation is proceeding; and when corporate mergers are no longer blocked as they were under the Biden administration? Normally, one would expect corporate investment to boom under those circumstances.

Again, policy-induced uncertainty is largely to blame. Besides the changes to trade and immigration policies, the Trump administration’s corrosion of past US norms regarding the rule of law, government corruption and self-dealing; technocratic provision of economic and scientific data; and central bank independence all take their toll. As the economic theorists Avinash Dixit and Robert Pindyck have shown, business managers tend to respond to rising uncertainty by dialing back on capital outlays for things like new factories, because such expenditures are largely irreversible.

The US under Trump is potentially facing a situation like the UK did in the aftermath of the Brexit referendum of 2016, which caused private investment to flatline for several years, depressing growth. AI investment and the plausible productivity gains resulting from it may well offset a lot of the contraction from the effect of tariffs and deportations taking hold in 2026. In fact, stimulus from the ongoing AI boom and looser fiscal policies will compound the inflationary pressures from Trump’s trade and immigration policies, as shortages of labor and imported inputs become more widespread.

That the full effects of Trump’s program are not yet visible doesn’t mean that mainstream economics was wrong. Rather, it’s indicative of the way uncertainty delays or even paralyzes decision-making.

Written by: Adam S Posen @Bloomberg

Adam S. Posen is president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, a nonprofit nonpartisan research institute in Washington, DC.

The post “The Economic Toll of Trump’s Policies Will Soon Be Visible” first appeared on Bloomberg